Around the Web

Amid Uncertainty, Youth Look to WYD Seoul 2027

The first comprehensive study ahead of World Youth Day (WYD) 2027 finds that economic hardship and career pressures afflict young people regardless of faith

【Seoul, South KOREA】 With the WYD in Seoul roughly two years away, the Catholic Church has completed its first broad survey of young people’s lives and beliefs, polling both Catholics and non-Catholics. The study is an attempt to understand the rising generation through data rather than anecdote—and to provide a basis for pastoral planning.

For decades, young Koreans have been discussed more often than heard. Since the early 2000s, they have been tagged the “880,000-won generation” and the “N-po generation” (those who give up N aspirations), and more recently the “MZ generation”—a cohort typically portrayed as fragile or in need of protection. Critics say the Church, too, has struggled to engage young people in any sustained way. As Seoul prepares to host World Youth Day, some argue that success depends on “understanding young people’s concerns and treating them as actors, not objects of pastoral care.”

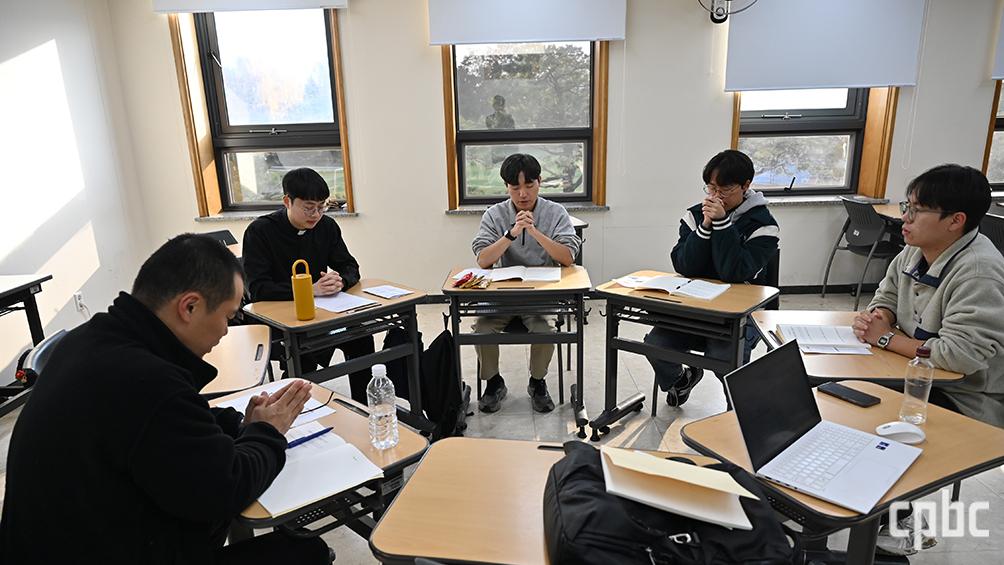

Commissioned by the WYD Seoul organizing committee, chaired by Archbishop Peter Chung Soon-taick, the research was conducted by a team led by Father Oh Se-il. A polling firm surveyed 1,973 young adults drawn from the general population and 2,278 young Catholics active in nine dioceses. Catholics aged 30–34 formed the largest subgroup, mirroring their prominence in parish youth activities. General respondents answered 88 questions; Catholics were given 111, including ones on synodality. The findings, organizers say, will inform a new framework for youth ministry.

Four in ten report burnout

The survey paints a portrait of young adults pressed by economic insecurity, job-market pressures, and relentless competition. Respondents described a cycle that runs from financial stress to anxiety about the future and a constant push to acquire credentials. Many reported burnout—and chronic distress from comparing their circumstances with those of their peers.

Anxiety cuts across denominational lines. Some 61.9% of Catholic respondents said they struggled with anxiety about the future, compared with 59.6% of the general population. Economic stress affected 66.8% of the general group and 58.6% of Catholics. More than half—62.5% and 58.5%, respectively—felt they must continually upgrade their credentials.

Four in ten respondents said they had experienced burnout, with rates higher among Catholics (48.1%) than among the general population (40.7%). Yet when asked whether they had anyone to rely on in difficult times, 30.2% of the general group and only 14.8% of Catholics said they did not, revealing a striking disparity in perceived social support.

Divergence from Church teaching

Even Catholics who espoused Church doctrine in principle diverged from official teaching on suicide, family life, and capital punishment. Some 42.3% of general respondents regarded suicide as ethically permissible, compared with 18.5% of Catholic respondents. Yet on euthanasia, large majorities of both groups (83.1% of the general population and 66.8% of Catholics) said it should be allowed—suggesting a strong preference for personal autonomy in end-of-life decisions.

On capital punishment, majorities of both groups—69.3% of the general population and 62.3% of Catholics—rejected the view that it is unethical.

More than four-fifths of both groups considered premarital sex and cohabitation acceptable. Support for premarital sex stood at 89.1% among the general population and 87.2% among Catholics; for cohabitation, 88.8% and 82.8% respectively.

Catholic young adults also showed openness to newer family structures. Same-sex marriage was supported by 59.7% of the general population and 50.9% of Catholics. A majority of Catholics (56.2%) saw no ethical problem with surrogacy using donated sperm or eggs—a view at odds with Church teaching.

Divides shaped by gender and politics

The research suggests that “faith alone no longer defines young people,” said Father Jeong Gyu-hyun of the Archdiocese of Seoul, who presented the first thematic analysis. Gender and political orientation, he concluded, create sharper divides than religious affiliation.

Among young Catholics, 40.1% of men identified as conservative or center-right, whereas 56.2% of women identified as progressive or center-left. Men prioritized “freedom and protection of rights” as preconditions for a just society; women emphasized support for the vulnerable.

Large numbers of young adults believe happiness is possible without religion. Three-quarters of the general population agreed. Among Catholics, 35% agreed—while an overwhelming 93.2% simultaneously said religion was important, a result that appears internally contradictory. More than 30% of Catholic respondents said they consulted fortune-telling, shamanism, or tarot.

Anxiety deepens generational rifts

A separate qualitative study, undertaken by the WYD Seoul volunteer spirituality team, explored the survey’s findings on anxiety through interviews with ten young adults. Using terms such as “generational relations,” “isolation,” and “conflict,” the team examined how anxiety shapes interactions between age groups.

Citing the final report of the 15th Synod of Bishops, Lim Na-kyung (Cecilia) highlighted the notion of “mutual alienation”: a condition in which “shared needs and goals disappear, and people drift apart without even clashing.” Generational tension, she argued, has evolved beyond conflict into a form of estrangement. Older adults, wary of appearing patronizing, withhold advice; trends such as “young-forty” (older people mimicking youth culture) signal not just conflict but a widening gulf.

Young Catholics reported similar feelings within the Church, where they expected solace but often experienced alienation. Interviewees cited the transmission of faith through obligation and guilt, being treated as unpaid labor at parish events, and an authoritarian ecclesial culture.

A call to treat youth as full participants

Lee Ji-woon, a researcher at Sogang University’s Institute for Contemporary Political Studies and a member of the Vatican’s International Youth Advisory Body (IYAB), argued that youth ministry must allow young people to act as “agents.” IYAB itself, she said, emerged because young Catholics demanded a voice during the 2018 Synod on Young People. WYD in Seoul, she argued, should be more than a one-off event: it should initiate a synodal process in which Church and youth “listen to one another” as “co-responsible partners.”

Bishop Lee Kyung-sang, the event’s general coordinator, said the Church must speak to the “social ills” fueling young people’s anxiety and consider initiatives such as public hearings to address them.